Contact us

401 W. Kennedy Blvd.

Tampa, FL 33606-13490

(813) 253-3333

Rachel Ryweck ’24 and Jacob LaFond, instructional staff in the Department of Biology, are experts on the most poisonous toads in the state.

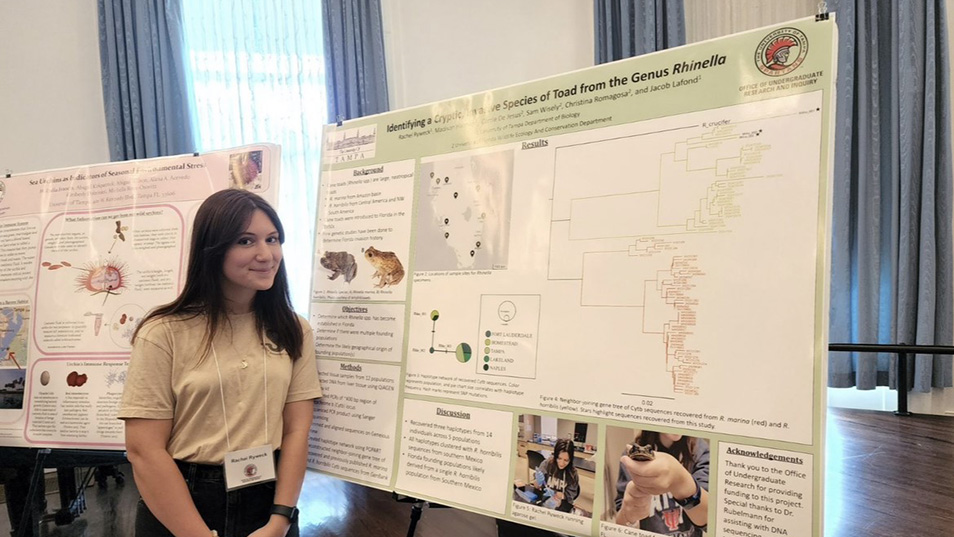

Rachel Ryweck ‘24 at the Summer Undergraduate Research Fund symposia. Photo courtesy of Rachel Ryweck

The two are researching the differences of several species of toads with the goal of understanding the differing DNA among them. By then tracking the DNA of the poisonous invasive cane toad species, Ryweck and LaFond can study the waves of cane toad invasions.

The research is informative, meaning the data will be shared with collaborators and may lead to finding a solution to the invasion. The goal is to remove the overgrown population of cane toads and restore Florida’s ecosystem.

The challenge is, the toads Ryweck and LaFond are studying all look identical. The doppelgänger species are called cryptic species, a newer term in the evolution of science.

Even the foremost expert on cane toads with the best microscope couldn’t spot a spec of difference between the brown, bumpy and impressively large species of cane toads because physically, the species are indistinguishable, Ryweck explains. Yet cane toad species are genetically distinct, which means they are classified as an entirely different species. Ryweck and LaFond have concentrated their work on two.

“If you do a bunch of genetic work, you can see that their DNA is slightly different and different enough that it’s two different species,” Ryweck explained.

So far, one species they’ve studied came from the Amazon basin and the other originated from Central America and northwest South America.

The anthropological approach can help document the evolution of these similar cane toad species and reflects an impressive, expanded cane toad empire: as far as Australia, cane toad species have flourished to the detriment of the local environment.

“We don’t know if different origins have certain diseases that they can spread compared to other origins,” Ryweck said.

However, the cane toads have already hurt Florida wildlife and even the everyday Florida citizen. If ingested, the cane toads are poisonous and can kill cats, dogs and native Floridian wildlife. The toads also eat anything in the ecosystem, even if dog food is left out.

The two started working together after Ryweck was interviewed to be a mentor for a biology class. Due to schedule conflicts, the position fell through, but LaFond was already impressed with Ryweck. She had mentioned in her interview the work she wanted to do in grad school on herpetology, the study of reptiles and amphibians.

He invited her onto the cane toad project shortly after.

Ryweck received a grant from the Summer Undergraduate Research Fund (SURF), which provides a student and their research advisor funding to collect and present research. The grant enabled Ryweck and LaFond to travel to Lake Placid in the middle of Florida with a group of researchers to find and collect cane toads.

The group arrived past sundown in a residential neighborhood, armed with protective equipment. The locals were suspicious at first but quickly grew enthused with the research project. The neighborhood warmed up to the band of scientists and would point out popular “hot spots” where the toads liked to habituate, Ryweck said.

An invasive cryptic cane toad. Photo by Lena Malpeli '25

Twenty toads later, Ryweck and LaFond began to document toad data. The findings will be shared with sister universities like the University of Florida, which also are doing research on invasive species.

When the project ends, Ryweck will apply to graduate school with the cane toad research on her application. LaFond plans to continue researching the cryptic toad species complex.

Both researchers expressed their appreciation for the project and their sorrow to say goodbye to the cane toads.

Most nuisances aren’t as cute as the cane toads, La Fond said, and he can’t help feeling a bit conflicted about them.

“It’s not their fault that they’re here,” he said. “They were brought here, and they’re just doing what nature intended them to do—go around and eat everything. They’re living their truth, and they’re adorable.”

Story by Lena Malpeli '25

More UT News