Contact us

401 W. Kennedy Blvd.

Tampa, FL 33606-13490

(813) 253-3333

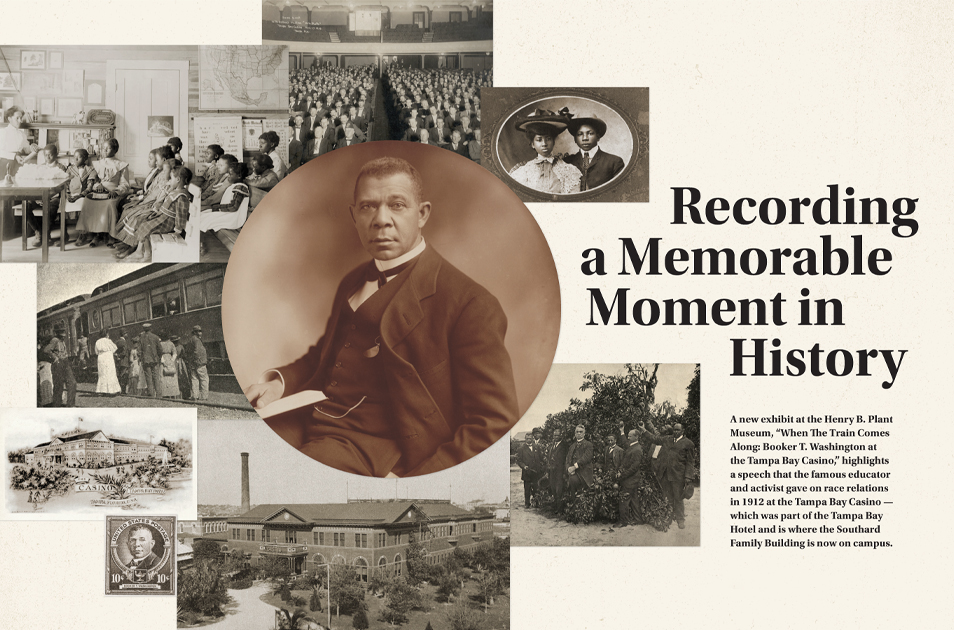

A new exhibit at the Henry B. Plant Museum, “When The Train Comes Along: Booker T. Washington at the Tampa Bay Casino,” highlights a speech that the famous educator and activist gave on race relations in 1912 at the Tampa Bay Casino – which was part of the Tampa Bay Hotel and is where the Southard Family Building is now on campus.

By Dave Seminara | Photographs Courtesy of The Henry B. Plant Museum

On March 4, 1912, almost two decades before UT was founded, educator and activist Booker T. Washington gave a speech on race relations to a white, Black and Latin crowd at the Tampa Bay Casino.

Charles McGraw Groh, associate professor of history, guest curated the exhibit. Photograph: Jessica Leigh

"Whites and Blacks heard different things from the speech, but they were both encouraged to work together. And that message is more important and necessary now than ever."

-David H. Jackson Jr.

Artifacts abound from Booker T. Washington’s past. Photograph: Jessica Leigh

Washington celebrated the achievements of Black entrepreneurs in Tampa’s cigar industry. These artifacts are on loan from J.C. Newman Cigar Co. and University of South Florida Libraries. Photograph: Jessica Leigh

More than 40 students who make up the University Chorus – directed by Rodney Shores, lecturer in voice – studied and recorded two spirituals, which were sung during Booker T. Washington’s speech at the Tampa Bay Casino in 1912. You can watch the students perform them online at plantmuseum.com/exhibits/online-exhibits/music-and-memory. Photograph: The Books of American Negro Spirituals

Emily Schurr ’21 designed the exhibit's guide for children who attend with their families. Photograph: Jessica Leigh

More UT News